Episode 118

Why Growing Your People Is The Ultimate Growth Strategy Your Business Needs To Prioritize Now With Ryan Heckman

If you want your company to scale, here's one question you need to ask yourself: Are you growing your people as fast as you're growing your revenue?

Too many leaders obsess over business expansion but ignore the foundation that makes it possible—PEOPLE.

In this episode of the Happiness Squad Podcast, Ashish Kothari and Ryan Heckman remind us that when you invest in your people’s growth, your business follows. Ryan reveals the leadership shift that can turn any stagnant company into an unstoppable force.

Ryan Heckman is a seasoned private equity investor with over 25 years of experience, currently serving as co-founder, managing partner, and CEO at Rallyday Partners, a lower middle market investment firm. He also co-founded the Colorado Impact Fund, a Denver-based social impact fund.

Previously, Ryan was the CEO and Chairman of EVP Eyecare and co-founded Excellere Partners, a private equity firm managing approximately $1.3 billion in capital. A two-time Olympian in skiing, he is also the Chairman of CiviCO, a founding board member of Endeavor Global/Colorado, and a Trustee at the University of Denver.

Things you will learn in this episode:

• Why growing your people is the fastest way to grow your business

• How leadership is not about control—it’s about empowerment

• Why culture should get better as a company grows—not worse

• Why leaders must be coaches, not just managers

• How trust and psychological safety drive performance

This episode will challenge everything you thought you knew about leadership and business growth. Don’t miss it!

Resources:✅

• Rallyday Partners: http://www.rallydaypartners.com/

• Colorado Impact Fund: http://www.coloradoimpactfund.com/

• CiviCO: https://www.livecivico.org/

• Intrinsic Value (Wall Street Journal Column by Roger Lowenstein) https://rogerlowenstein.com/

• First Biography of Warren Buffett – By Roger Lowenstein: https://hbr.org/1996/01/what-i-learned-from-warren-buffett

• Research from the Michigan Ross Center for Positive Organizational Scholarship: https://positiveorgs.bus.umich.edu/an-introduction/

• Clay Christensen's Work on Management as a Noble Profession: https://hbr.org/2020/01/clayton-christensen-the-gentle-giant-of-innovation

• Jan-Emmanuel De Neve & Sonja Lyubomirsky (Oxford Research on Workplace Well-Being): https://d341ezm4iqaae0.cloudfront.net/ews/20220817145319/Work-Wellbeing-2022-Insights-Report-.pdf

Books:✅

• The Heart of Business by Hubert Joly: https://a.co/d/eVeJrY1

• Grow the Pie by Alex Edmans: https://alexedmans.com/books/

• Hardwired for Happiness by Ashish Kothari: https://a.co/d/5G5k5IX

Transcript

Ashish Kothari: Ryan, I am so excited to be recording this podcast with you, my friend.

Ryan Heckman: Yeah, well, we started our friendship at Chautauqua Park in Boulder. I remember we walked almost seven miles, and it felt like five minutes because you and I were just like, yep, yep, yep, yep, yep, yep, yep.

At the end of that walk, I felt such a kinship with you—intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. It's so interesting how we both came from environments that were very performance-oriented. In your case, McKinsey, and in my case, Private Equity.

We've both reached places in our lives where we can explore the unknown. It's just fun to do that with someone like you—someone who thinks so far outside the box and has the right brain, the left brain, and the heart completely synchronized and on fire. It's just fun to be with you. So, this will be a fun hour—or whatever this ends up being.

Ashish Kothari: Yeah, an hour or three hours! I know it's Friday, and we have to get going. I feel the same, Ryan, about you. In fact, I'll share this funny story of how we actually got connected.

On a Saturday, I usually have a yoga sequence, and I was doing my yoga while listening to a YouTube video or a podcast. And there you were—with Raj Sisodia!

I thought, "Wait, here's Ryan. Private equity? Wait, what are we talking about?" I literally texted you on LinkedIn, and you got back 10 minutes later. That’s how our relationship started.

Then we met, and what was supposed to be an hour-long walk turned into a three-and-a-half-hour journey through Chautauqua. Man, I’m so excited to share your story and the work you’re doing because I feel the same way about you.

Oh, and for our listeners, you and I are almost exactly the same age—born two days apart, March 7th and March 9th.

Ryan Heckman: I can't believe we're both 40. That’s just so weird.

Ashish Kothari: Exactly! But listen, I want to take this conversation through a bit of an arc because I know I wasn’t born this way. I lived my first half-mountain journey in a very structured way. It helped me a lot and is still a big part of what I do. But then I found something else. So, I want to trace that origin story for you too.

Talk to me a bit about your journey. You competed as an Olympic skier. You’re a two-time Olympian. And I’ve served on the USA Olympic Committee and with U.S. Gymnastics, so I know what it takes.

People think they know what it takes, but I really know because I’ve been in the rooms with these athletes. The level of discipline, resilience, and focus is extraordinary—and you have all that.

I’m curious—looking back at those foundational years, the first 14, 15, 16 years of your life leading up to your highest achievements—what were some of the lessons you took from that time that still help you to this day?

Ryan Heckman: Well, I would start by sharing that I rarely talk about my athletic life. It can very quickly sound like a humble brag or just flat-out bragging. The irony of it is that my skiing career, which lasted from the age of 9 to 21, was so formative yet so humbling in how I felt.

I could count on one hand the number of times I felt cool during that time. Perhaps when I was in Seventeen magazine—when I couldn't get a date. I was very underdeveloped, had huge ears, and no girls would talk to me at 17. But when I was in Seventeen magazine, I suddenly became super cool.

Another time was marching in the opening ceremonies for the first time, surrounded by so many people I admired. I felt cool then.

Beyond that, my life was filled with discipline, solitude, and loneliness that it never felt glorious. It's a fun topic, but whenever I bring it up, it can sound like, Oh, he wants to talk about how cool he is because of his skiing career. I just want to preface that because while I’ll share some of it, I’m often reluctant to talk about it.

The quick version of my story is that I wasn’t very good at other sports, nor was I good at school. I tried basketball, football—I even tried wrestling with the headgear and singlet. They had weight classes, and to give you perspective on my size, my driver's license at age 16 said I was 4'10" and 105 pounds. I sucked at all these sports.

And because I also wasn’t great at school, I was desperate to find something I could be good at. For one reason or another, I was very good at skiing and progressed rapidly.

When I was 10, I wrote a paper for school—it was either third or fourth grade—about what I wanted to be when I grew up. I said I wanted to go to the Olympics. The amazing part was that just six years later, I was walking in the opening ceremonies at the Olympics in Albertville, France. That’s such a short amount of time.

Ashish Kothari: Yes.

Ryan Heckman: When you think about envisioning something, executing on it, and having the resilience to push through—it’s incredible to come out the other side at such a young age.

I think I was the youngest Olympian at those Olympics in any country. I was definitely the youngest from the United States.

At that same age, I left home, which had some trauma associated with it. I lived in my truck at the base of a ski area intermittently through the winter. But amazingly, I never felt underprivileged or that I was facing adversity.

I thought, I want to go to the Olympics. I want to do this. This is part of my training. This is what it takes. It never felt beneath me. I took showers at the local pool. Taco Bell was where I ate most of my meals—I rotated between McDonald's, Wendy’s, and Taco Bell.

It didn’t feel weird. My mom gave me a gas card for the Amoco station and basically told me, Don’t tell your dad. That station went out of business six months later, but it was where I bought groceries.

Eventually, a family let me live with them. That was a big moment for me. It was the first time I noticed the feeling of walking into a home and sensing security—the smell of a home-cooked meal.

I remember the first time I walked into their house after living the way I had for a year. I just felt relieved, loved. It was definitely a strange way to grow up. There is no doubt. My son is 16 now, and when I look at him, I can't believe I was doing that at his age.

Being an international competitor, one interesting thing I realized was the contrast between training and competing. In the business world, we spend 95% of our time executing or competing and very little time training. That’s a huge difference from the competitive sports world.

Another difference is that in an individual sport—unlike a team sport—you pretty much lose all the time. In a team sport, all else being equal, you have a 50% chance of winning. But when you're competing against the 100 best athletes in the world every weekend, there's only a 1% chance of winning.

I had to become very comfortable with the process—the inputs—and take pride in those inputs because I rarely got to win. I had to trust in the process, take pride in my work, and detach from being seen as a “winner.”

That mindset helped me tremendously in business. As a CEO, I felt like every day was just a series of problems I had to solve. Rarely did I go home thinking, Great job, Ryan! And no one at work was going to pat me on the back either. It was a similar temperament to what I had to adopt as an athlete.

I also learned the power of coaching. Interestingly, my favorite coach wasn’t the one with the best technical ability. In fact, he was terrible at the technical side. But what made him so special was that I knew he believed in me so much.

When he gave me advice, it came from a place of seeing and loving my potential more than my present state. I clicked with that.

When you're on top of a ski jump—just for context, I was a ski jumper—you're up there alone. Sometimes there's a jumbotron, and you can see yourself on the screen, which is surreal. It’s windy, it's dangerous, and your coach is down below on a little stand. Once you push off, there's no turning back.

If you know your coach believes in you, you perform better. I always performed better when my coach was there. That relationship shaped how I work with CEOs today. I want them to feel that from me—that I believe in their potential so much that I’m willing to have the hard conversations, give them tough feedback, and push them.

If they know I believe in them, they’ll receive it the way I did as an athlete.

Lastly, resilience. It’s an overused word, but it matters. It’s like grit. We talk a lot about resilience, but being an athlete means constantly crashing, failing, picking yourself up, and grinding it out.

In business, success isn’t about being the smartest. It’s often about who can outlast the critics, who can endure discomfort the longest. The compounding effect of living in discomfort for an extended period translates into incremental personal growth.

I’ve lived in discomfort since I was 10 years old. That discomfort has translated into significant personal growth over the years. Those would be some of my high-level observations about that period of my life.

Ashish Kothari: Look, I mean, I love each and every one of them. I can see how shaping they can be—all the way from not being afraid to fail, which so many teams talk about. But it's often just a cognitive concept.

As you describe it, I can feel it. Yeah, I'm going to not win, and that's okay. Because the moment I let that fear in, all of a sudden, I know it's over.

Ryan Heckman: What I attached myself to, which is really helpful in business, is progress.

Ashish Kothari: Yes.

Ryan Heckman: Any of us can come to work and make progress every day. You may not get the EBITDA that you want. You may not get the outcome that you want. But it’s actually a pretty low bar just to move the ball forward—even an inch.

If you do that enough times, over enough days or years, it adds up. That matters. With our businesses, I talk a lot about return on effort. Progress is more important than winning.

Ashish Kothari: Yes, progress over perfection—any given day.

Ryan Heckman: All day.

Ashish Kothari: All day long. Just take that step forward. If you stumble, it’s your choice what learning you take from it. Take the learning or don’t, but then move on and take the next step. And the next step. Over time, you will get there—especially if you have someone who truly believes in you and is there, guiding and supporting you on your journey.

Ryan Heckman: Yeah, we have a little illustration or logo on our website that says: We want to be your first call on your worst day at Rallyday.

That comes from this place of emotional safety—our CEOs knowing that we've had those bad days too. We want to be there for them.

In many other business relationships, you might be afraid to tell your boss—or whoever it may be—the bad news. Because the reality is, business is often just a series of bad news every day, and you’ve got to get through it.

We want to celebrate that rather than be critical of it.

Ashish Kothari: I want to pick up that thread, Ryan. As you said, you are a very different kind of private equity firm. I worked with a lot of private equity firms during my time at McKinsey, and you're different.

Most CEOs wouldn’t even think twice about calling their PE firm—even on their best day—because they’re thinking, Oh my God, they’re just going to give me the next target and say, ‘Go do more.’

Ryan Heckman: That’s really well said.

Ashish Kothari: They think, Let me just sit for a bit. Let me at least have the weekend. Let me enjoy this milestone before they give me the next one.

Ryan Heckman: Let me enjoy this milestone before I'm given a new one.

Ashish Kothari: Exactly. But you actually want to be the person they call. You want them to know, We’ve got you. We invested in you because we believe in you and in what you're trying to do.

Talk to me about that, Ryan. That’s one element. But tell me more about how Rallyday—the firm you built with your partners—is really different.

What’s the core vision? We’ll circle back on why, after 20 years in traditional private equity, you started it. But first, tell me about the core vision behind Rallyday.

Ryan Heckman: Yeah, it's hard for me to separate my personal journey from Rallyday, but I'll do it since you've asked me to.

Ashish Kothari: Then tell the story. Tell the whole story of how your experiences led to this. Do the arc that feels most natural.

Ryan Heckman: Okay. Yeah, I apologize for being difficult, but the Rallyday story is just inseparable from where I came from.

When I ended my skiing career, I didn’t really go to high school all that much. The winter season happened to coincide perfectly with the academic season. I would usually go to Europe in early October and come back in April. I spent all my time over there and didn’t really go to school.

I once rode on a plane with a guy who worked in private equity. His name was George Gillette. By the way, he’s a McKinsey alum. I can’t recall the years, but that’s not really relevant. I was on a flight with him from Dulles to Zurich, and I literally talked this poor guy’s ear off for eight hours.

He was with his wife, and I can’t believe he let me do that. But I wasn’t just talking his ear off—I was absorbing his life experiences. I think he had fun telling me his story. It was like an eight-hour podcast. But looking back, I feel bad for his wife. She must have been so mad that he didn’t sleep at all on that flight. He probably landed horribly.

I think I was 17 at the time. When we got off the plane, he turned to me and said, Hey, if you ever get a college education, give me a call.

When I stopped skiing, I did go to college. I applied to Stanford, and funny enough, I basically got a cease and desist order from them. It wasn’t even a standard rejection—it was like, We don’t even want you coming to California.

My application was so bad. I remember spending days writing that essay—something that would probably take me an hour now. But I was so ill-equipped and had no idea what I was doing. I was very naive.

So I went with my backup plan—applying to the University of Colorado in Boulder, our state school. And I got denied there too. At that point, I thought, Oh my gosh, I am in so much trouble. What did I do with my life?

I had to look failure in the eye at that age. The librarian from my high school helped me get in through the backdoor at CU. I was on probation for two of the three years I went to school there, and I was woefully behind my peers.

One moment that stuck with me—I was in an introductory science class, probably biology, one of those required courses. I looked around the lecture hall—there were about 500 students—and I felt completely anonymous.

I had gone from being an elite Olympic athlete to just another face in the crowd. Then I had a second thought: Not only am I irrelevant, but I’m probably the dumbest guy in this whole building.

It was such a stark contrast. I had gone from being the best in the room to being the worst. That realization hit me hard. How did I let this happen? What in the world? That moment really motivated me to work harder in college.

For example, I had to start over in math with basic algebra. My 13-year-old daughter was doing algebra last year, and it was crazy to think I was doing it at 21. It was a humbling time in my life, but I ended up doing pretty well.

One of the biggest changes I made was reading The Wall Street Journal every day. That became my new training. Since I was no longer training for skiing, I replaced that with reading The Wall Street Journal cover to cover.

I became friends with Roger Lowenstein, a contributing writer for The Wall Street Journal. He wrote the first biography of Warren Buffett and had a weekly column called Intrinsic Value, where he tried to teach how businesses were valued. He took that concept from Buffett, who likely took it from Benjamin Graham. I was fascinated by it.

One day, I called The Wall Street Journal’s 1-800 number and asked for Roger Lowenstein. And he answered. Anytime I had a question in school, I could call him. That became a coaching relationship for me. I got really attached to that process—the two or three hours I would spend reading every day.

To this day, I still do that. Every morning, even on weekends, I carve out two or three hours to read.

When I finished college, I called George Gillette—the guy from the airplane—and said, George, I graduated from college. Do you still remember me?

He said, I do. Meet me at Monday Night Football—Raiders vs. Broncos at Mile High Stadium—and let’s talk about your future. So I met him in the parking lot at Mile High Stadium, and he asked, Do you want to work for me?

I said, I would love to.

Then he asked, How much do you want to make?

At the time, I thought $40,000 was a huge salary. My mom had told me that was the peak wage. So I said, $40,000.

He replied, How about $37,500?

I said, Done.

We shook hands, and he told me his assistant would be in touch. That’s how I got into private equity.

I was only 23, and it was a very thin team. We did a ton of deals. My last project for him was buying the Montreal Canadiens hockey team.

After that, I moved into a more institutional private equity job and did that for another 10 or 11 years.

By the time I was 40, though, I became almost disgusted with my industry. I didn’t like the people in it. I thought they were arrogant and narcissistic.

I didn’t like the way my firm communicated with executive teams. I didn’t like the do as I say, not as I do attitude—the preachy way private equity firms handled relationships.

I was at a conference in Orlando, Florida—2,000 private equity guys, all wearing blue blazers and lanyards. I looked down and realized I was wearing the same thing. On my flight home—a three-and-a-half-hour flight—I decided to quit.

Everyone in my family and all my friends thought I was crazy. They asked, What are you doing? I suppose it was a midlife crisis. Raj, who you mentioned, would probably call it an awakening.

When I told the CEOs I worked with, they said, It’s about time. Go build something. Go lead people. Get a real job.

The problem was, no one was going to hire me. So I bought a small business with 11 employees. It was a healthcare business. The clinic was on campus, but my office was in a tiny space above a Men’s Wearhouse. I had to walk through the tuxedo section to get to my office. And they weren’t nice tuxedos.

I built that business over five years from 11 employees to 450. We became the dominant player in Colorado, Texas, and Arizona. I built it to $13.5 million in earnings.

I stretched every dollar—I built it with only $3 million in capital. Eventually, I ran out of money and needed capital to keep growing. My only option was to sell to a private equity firm.

One thing I never did was pay myself a dime.

Because I knew I was woefully inadequate in leadership, HR, and people management, I hired an executive coach—not just for me, but for the entire company. I wanted to teach everyone how to become a leader. I think that’s why we were successful.

For many people in healthcare—whether doctors or front-desk staff—they never saw themselves as leaders. But when we gave them leadership training and set the expectation that everyone was a leader, it changed everything.

We called it leading your 20 square feet. They knew I was on this journey with them. We were all just trying to grow as people so we could grow the business.

That experience led to one of the core principles of Rallyday:

We don’t just have a responsibility—we have an obligation—to help the people in our companies grow. Because when they grow, the business grows.

It sounds simple, but not many people in my industry think that way. That principle has helped us succeed so far, and I believe it will continue to serve us well in the future.

Ashish Kothari: Yeah, I would say, first of all, Ryan, thank you for that. Thank you for that walkthrough.

Our experiences shape us into who we are, and they create certain beliefs. That was a really pivotal and beautiful story of how you came to see the world this way.

By the way, you said, in my industry, people don’t see it that way. Unfortunately, I think today, in the world of business, people don’t think about it that way either. They don’t think about the fact that businesses are, in the end, the net result of the people within them.

If you invest in the growth of the people, the growth of the business is exponentially greater than you ever imagined. But if you grow at the cost of people, you create a drag on performance.

I was sharing this with you before—the person whose work really proves this. When I talk about this work, I tell people, Don’t do it just to be nice to people. Don’t do it because you’ve had some moral awakening about being a better leader. Do it because it is a financial and fiduciary responsibility as a board member, an executive team, and a leader.

Here’s the research. Here’s the data. You can generate 2 to 3.5% higher shareholder returns when you truly invest in your people. And this is measurable over long periods of time.

Let’s talk about well-being. The latest Oxford research by Jan-Emmanuel De Neve and Sonja Lyubomirsky measured workplace well-being across thousands of companies. You can even go online and look up any company’s workplace well-being scores.

on workplace well-being from:That’s real.

But most people don’t think about it that way. They don’t take the long-term view. And I think that’s because no one ever invested in them—so they only know one way to lead.

What you’re trying to do, and the core tenet of your approach, is a game changer.

Ryan Heckman: But isn’t it ironic that I fell into this because of my own inadequacy? It’s kind of wild when you think about it. I felt insecure and inadequate in this area of business because I had never done it before.

I was trying to grow a business, and through my own desire to grow, I stumbled my way into a leadership equation that I had never read about.

Only in a few instances—including our conversations—do I hear people using this kind of language. It’s just not out there.

Ashish Kothari: It’s not out there.

Ryan Heckman: It’s literally right under our noses—meaning, it’s in our hearts. It’s right there, beating every day.

Anyway, I find that fascinating.

When I finished building my business and sold it to a private equity fund, the buyers were perfectly good people with great integrity. But the experience was horrible.

We had monthly board meetings, and I would spend a week with my CFO and the rest of the C-suite putting together the board deck. Then, we’d get beaten up for six or seven hours in the meeting.

After that, I’d spend another week helping my team rebuild their confidence—including my own.

It was exhausting. The experience of building a business had gone from the best thing I had ever done to one of the worst.

So we started discussing a succession plan. We hired my replacement, I moved into the chairman role, and then I was left asking, What am I going to do with the rest of my life?

I was only 45 at the time, so I could have kept buying small businesses and building them. Then I ran into a very dear friend of mine, Nancy Phillips. She had just sold her business—for the fourth time. She had moved to the chair role and had similarly difficult experiences with four different private equity firms over her career.

I should mention, Nancy built her business over 20 years from zero to $120 million in EBITDA. At dinner one night, I asked her—she’s Canadian, so she’s not very prideful and sometimes apologetic about her own success, which I make fun of her for all the time—What are you most proud of?

She had just sold her company for $1.7 billion. A massive success. At first, she gave me some generic, humble answers. But I pushed her: No, come on, Nancy, tell me the truth.

And she finally said, Actually, here’s what I’m proud of. I grew personally faster than the business did and more than the business ever did. That’s what I’m most proud of.

I just sat there, thinking, Oh my gosh, I’ve found my soul sister. From that conversation and that bond over that principle, we decided to form Rallyday.

k we raised our first fund in:It’s interesting how life’s twists and turns lead us to where we are. Rallyday is built on another basic principle:

If the function of our firm is to build legendary businesses—and we work in the smaller end of the market, where there’s more building than managing—then the leadership model has to be different.

There are roughly 4,500 private equity firms in this country. I’d say 99% of them are run by former investment bankers, consultants, or other quantitative professionals. And they’re trying to teach or coach CEOs—without ever having done that job themselves.

Ashish Kothari: Right.

Ryan Heckman: And so that happened because you can't have a private equity fund without capital. The investor community doesn’t quite understand that it’s very difficult to coach someone on how to do something if you’ve never done it yourself.

Imagine trying to teach your kids how to ride a bike if you’ve never ridden one yourself. Or teaching them how to swim when you’ve never swum. It just seemed so obvious to us.

What’s cool about Rallyday is that all of the managing partners have not only been CEOs, but they’ve also been founders. They’ve stumbled, they’ve failed, and they have a lot of texture and humility.

That really changes the relationship we have with our leaders. It also shapes the culture within our firm in a way that’s very different from the typical private equity leadership style.

Ashish Kothari: Yeah, absolutely.

By the way, you were talking about how amazing it is that you fell into this because you were coming from a place of not feeling like enough. That made me reflect on how our origins shape us.

We don’t choose the things that happen to us. But our experiences shape us.

As a skier, you knew it was okay to fail. You knew it was okay to acknowledge when you didn’t know what the hell you were doing.

Most people wouldn’t do that. They’d think, I don’t know what I’m doing, so I better not tell anybody. I better make myself look bigger than I am because otherwise, they’ll find out.

Second, you understood the power of a good coach. You knew that even though you were at the top of your game, you couldn’t keep improving without the right coach.

So when you needed help, you were willing to pick up the phone and say, Hey, I don’t know this. Can you help me? And even more than that, you were willing to say, Can you help others too? And let me share with them that we’re all in this together.

Most people wouldn’t do that. Even if they had a coach, they wouldn’t want others to know. They’d think, If people knew I had a coach, they wouldn’t have taken me seriously.

Ryan Heckman: I’ve never thought of it that way. I suppose my competitive skiing background did shape me in that way. The way I found my executive coach is kind of funny.

I had just done my first add-on acquisition—maybe my second, I don’t remember exactly, but it was early days. I was trying to do everything myself, and I was doing everything poorly.

It was two or three in the morning, and I couldn’t sleep. I had my own money in the business, performance wasn’t going well, and morale was really low. I was at an all-time low in terms of confidence.

I was watching PBS—Charlie Rose was interviewing Urban Meyer, who was either coaching at Florida or in the process of taking over at Ohio State program.

Meyer shared a story about how he once had an anxiety attack so intense that he passed out. His wife found him facedown in the living room. It was a combination of stress and fatigue. He had hit rock bottom from a well-being standpoint.

That’s when he reached out to an executive coach named Tim Kight. Urban Meyer talked about how transformational it was to work with Tim. Tim helped him develop a cultural system that was more reliable than himself.

By having a system to depend on, he no longer felt the anxiety of having to show up perfect every day for his team.

There was a dual benefit—this system enhanced the performance of his athletes while also helping him show up as a better human being. It reduced his anxiety—not just with his team, but with his family as well.

I was sitting there in my basement at three in the morning thinking, This is perfect. I have to find this guy.

The next morning on my way to work, I searched online and found Tim Kight’s contact information. I called the number, and he and his son became my coaches for the next five years.

So my failure and insecurity led me to this system.

Funny enough, all of that cultural architecture—the system of elevating the performance of people in an organization—we now use at Rallyday across all of our companies. That’s our culture module.

It’s just an interesting, funny part of the story.

Ashish Kothari: Yeah, I think it’s fascinating. These are the kinds of experiences that make your approach so different. Talk to us a little bit about your leadership development process.

You have a really interesting way of ensuring that the companies you partner with—and I won’t even say just invest in—truly benefit from this nontraditional, yet incredibly powerful and needed approach. Many of my mentors at Michigan Ross call this positive deviance.

Ryan Heckman: Say it again.

Ashish Kothari: They call it positive deviance.

People often associate deviance with something negative. But it’s not. Deviance just means doing something different from the norm.

And these practices can help leaders be positively deviant time and time again.

Ryan Heckman: I just love that. I will give you attribution, but I will probably use that later today.

Here’s the deal.

In private equity, the major KPI—the thing on every firm’s website—is assets under management (AUM). If you ever find yourself at a conference in Orlando with 2,000 other private equity guys, the question everyone will ask and have to answer is, What’s your AUM?

We hate those words.

First of all, we don’t look at it as assets—we look at it as people. People have chosen to let us invest in their companies. Calling a collection of human beings a collection of assets is just really sad if you think about it.

The word under is also demeaning. We like to think we’re under the company, supporting them—not over them.

And then there’s the word management. Some people tell me I’m wrong here, but I think management is a primitive form of leadership. Management is about functional control, but leadership is heart work, not just mind work.

So, all of that language is just terrible. And words matter to us. That’s why we don’t use that expression.

Once you make the leap to saying, We’re leading people, then the next question is: How do you lead people to build a better organization?

In the first six months of every investment, we have something called RAP—the Rallyday Accelerator Program.

A lot of people assume the word acceleration in this context means we’re trying to accelerate growth. But when we built this system, the goal was to accelerate trust.

We asked ourselves, What if we could build the same level of trust with the executives in the first six months as we typically do at year five? How would that change the quality of our conversations? How would it impact transparency?

People throw around the word transparency all the time, but there are two parts to it. Someone has to be vulnerable enough to share, and they’ll only do that if they trust the person they’re sharing with. That trust creates the emotional safety needed for real transparency.

So, in the first six months, we start with purpose.

We have a wonderful partner in this work—Haley Rushing. Haley worked with Herb Kelleher at Southwest Airlines, helping to build Southwest from the inside out. Herb hated advertising. That’s why, to this day, Southwest uses employees in its commercials.

His philosophy was that if employees find meaning in their work, they will go above and beyond—not because they have to, but because they want to. And when people want to do their work, the customer experience is fundamentally different.

That’s why Southwest feels different from, say, United Airlines.

Haley worked with Herb for 12 years to build that culture. Since then, she has done purpose work for Whole Foods, Airbnb, BMW, Walmart—you name it. When she works with our companies, she leads them through a stakeholder scan to answer one core question:

Why does this company exist?

Ashish Kothari: Why does it exist? Yeah. Why?

Ryan Heckman: Why do employees work there? What brings meaning to their work? That work leads to a purpose statement for every company we invest in.

Then, the second module after purpose is strategy, which is table stakes. But the difference here is that whatever strategy we choose is in service of that purpose.

The third thing we do is ask: If this is our purpose and this is our strategy, what changes do we need to make to our culture to execute that strategy?

How specific do we need to get in defining behaviors so that it’s more likely we’ll achieve that strategy?

And importantly—if our strategy is to triple in size over three years—do cultures usually improve as companies grow? Or do they usually get worse?

What’s the answer?

Ashish Kothari: Mostly, it gets worse.

Ryan Heckman: Exactly. Study after study shows that as companies grow, their culture tends to decline.

Ask early employees, Did the culture get better or worse as the company grew? Most will say, Oh yeah, when we grew, the culture went to shit.

Our standard is that a good culture should get better with size, not worse. That’s really hard to do.

Then, we end with leadership development.

Now, there are different kinds of leadership development, and we’re still in the early innings here. We start with the executive team—that’s pretty straightforward. If you go to Amazon, there are 104,000 books on leadership. Most of that content is directed at the C-suite.

A lot of leadership books—some of which I think are over your shoulder there, Ashish—are made for L1s or L2s. That was relatively easy to get our arms around.

The second layer down—middle management—is more important, and there aren’t a lot of books for them. Middle managers are the connective tissue between vision and reality. They make the trains run.

We had to build a lot of content for them in-house. Our architectural team, who you know well, has been developing that content.

It covers things like how to have a one-on-one, how to give and receive feedback—basic but critical skills. People assume middle managers know how to do these things, but they often don’t.

Typically, middle managers were great individual contributors who got promoted—but no one ever taught them how to lead.

There’s a huge gap between the content available for them and the need they actually have. We’ve spent a lot of R&D time on that. Now, we’re just starting to focus on the frontline—and that’s where you’ll see my eyes really light up.

The frontline is where the company’s vision and strategy become a real experience for the customer. Think of a shoe company—somebody sells those shoes. That’s the frontline. That’s how the company is perceived by customers.

And yet, frontline employees are often hourly workers. If you go to Amazon and search for leadership books for hourly employees, you’ll find a grand total of zero. So, we had to start from scratch. And we can talk about that later.

Ashish Kothari: No, no. This is where I think we are so in sync. You’ll have to come over for dinner because 80% of the books behind me are actually about middle and frontline leadership. It’s a very different field.

The top shelf behind me is full of research from Michigan Ross’s Center for Positive Organizational Scholarship—people like Kim Cameron, Jane Dutton, and Bob Quinn.

They’re all in their 70s now, but they built the architecture of how certain cultures outcompete, outperform, and drive positive deviance by unlocking human potential.

Ryan Heckman: Ooh, I love that expression—unlock human magic. That’s good.

Ashish Kothari: There’s so much research on this, but unless you go looking, you don’t find it.

I spent my first 20 years working with CEOs and CXOs, telling people what to do. But once I shifted my mindset to enabling people—helping them build skills, giving them trust, giving them a voice, and letting them loose—things changed.

Instead of six initiatives, you get a thousand initiatives because people own them. They feel empowered to go and crush them. But for that, you need the right strategy, and you need the right purpose.

There’s so much alignment here because I think you’re really onto something amazing. There’s a lot of research, and we’ve curated a lot of material on this.

On your purpose-driven approach, I love it. Alex, whom I quoted earlier, has this line that I think captures it well. A lot of people think about purpose as just words on a wall. But that’s not what you’re doing with your companies. That’s not what Haley has done.

The right way to think about it is this: Performance through well-being, rather than performance at the cost of well-being.

Purpose is a huge ingredient of well-being. It’s a huge ingredient of flourishing.

Here’s what Alex said: "If you want to reach the land of profit, follow the road of purpose."

If you want to be profitable in the long term, purpose is the road that gets you there. Here’s why that’s important.

At McKinsey, we studied purpose in most companies. We found that 85% of senior leaders—the OGs, the ones making all the big decisions—said they found their work meaningful.

When you ask the frontline? 15%. Just 15% of frontline employees say they find their work meaningful. Think about that frozen middle and the frontline disconnect.

That means, for the majority of employees, all you’re getting are their arms and legs. You’re not getting their hearts and minds. For them, work is just a way to survive. I work here so I can live my life.

That’s why we see so much stress, anxiety, lack of meaning, and disengagement. If the majority of your waking hours are spent doing work that has no connection to your soul—no sense of meaning—how can you flourish in life?

You’re languishing for the biggest chunk of your day. Combine that with a lack of skills for handling conflict—where different perspectives could bring people closer and create something magical—and what happens?

People find work draining. They don’t find meaning in it. And on top of that, they’re constantly looking over their shoulder, worried about getting fired. They don’t trust their environment.

Ryan Heckman: And then their boss tells them, You need to smile when you talk to a customer.

Ashish Kothari: Exactly. Hey, we’re all about psychological safety, right? But then, if a customer complains, they’re fired. And yet, companies think they’re fixing this with Manager Appreciation Week—what, once a year?

Oh, I appreciate you once a week. What’s your problem? You should smile 365 days a year. This is the kind of broken thinking that’s everywhere. By the way, if you haven’t read this book, you should—Hubert Joly’s book on the Best Buy transformation.

Ryan Heckman: Can you text or email that to me later?

Ashish Kothari: I will. It’s called The Heart of Business. Joly highlights how, in his 10 years leading Best Buy, they followed a roadmap exactly like what you’re doing. They started with purpose, followed with strategy, and translated it into behaviors.

Before he took over, Best Buy was just the largest electronics retailer. Their job was simple—sell electronics. If you were a Best Buy employee, your job was: A customer walks in? Ask them what they need. Oh, they want a stereo? Show them the latest model. And, of course, upsell them.

Then they did purpose work and fundamentally redefined their mission. Their job was no longer just to sell electronics. Instead, their purpose became: To use technology to make a positive difference in people’s lives.

That changed everything. Now, when a customer walked in, the job wasn’t just to sell—it was to understand what they actually needed and help them use technology to improve their lives.

Now they weren’t just pushing the latest model. They were creating solutions. That shift led to innovations like Geek Squad and services to help seniors feel comfortable using technology in their homes.

And here’s the crazy part—80% of Best Buy’s workforce didn’t change. Yet, those 10 years were the best in the history of the company. Meanwhile, Circuit City went bankrupt.

Ryan Heckman: Yeah, they went bye-bye.

Ashish Kothari: Exactly. That’s why I love what you’re doing. You’re speaking truths that people don’t think about. Nobody trains the middle. Nobody.

If we can train middle managers to execute better, to lead better, to truly unleash that untapped human magic—What becomes possible? It’s something that no amount of top-down leadership can ever achieve.

Ryan Heckman: You know, I think there's something in there for us.

There's a guy named Bob Chapman—I don’t know if you’ve heard him speak. He runs a large industrial business in the Midwest. It might seem boring from the outside, but it’s anything but boring.

Bob was on a podcast, and he shared this story about having dinner with a private equity investor—a well-known guy.

Bob asked him, What are you most proud of?

Because Bob has this spiritual presence, people often step into something deeper than just, Oh, I manage a trillion dollars of assets.

So, the private equity guy tried to give a good answer. He said, Obviously, I’m proud of the business I’ve built. But what I’m really proud of is that my wife and I set aside a lot of money to fund scholarships for 30 underprivileged students in Florida.

Bob, being kind of a disagreeable guy, responded, That’s cool. But not that cool.

The private equity guy was confused. What do you mean?

Bob asked him, How many employees are in your companies?

The guy thought for a moment. We own about 80 companies. The average company has around 1,000 to 2,000 employees. So, I’d guess we employ about 150,000 people.

And Bob said, What if you gave all 150,000 of your employees an opportunity to grow? What if your platform provided them and their families a better way of living? How would you feel about your job then?

His point was that the idea of giving back philanthropically—after you’ve been successful—is a missed opportunity.

Because when you’re in business—at any level—you already have an opportunity to touch lives. And in private equity, it’s on steroids.

I don’t know how many employees we impact through our investments, but I feel a sense of calling and pride that is completely different from the financial outcomes we produce.

We’re giving people permission, support, and content that allows them to grow. They go home as better people.

And I can’t tell you how good that feels.

It took me a while to find meaning in my own work at this level. But now that I’ve found it, it doesn’t feel like work anymore.

Ashish Kothari: It doesn’t. It does not, right?

Especially when you make that deep connection, as you did for yourself.

I went from a world where I was really good at work-life balance. I was really good at it.

Ryan Heckman: I don’t believe that for a second. When you were at McKinsey, you were working your ass off. It was work balance. Not work-life balance.

Ashish Kothari: Fair enough.

For my first 20 years, I was mostly work. But in my last five years, I worked 36 hours a week—three to three and a half days. I served one client, and I did the work I wanted to do.

That was real work-life balance. Then, I shifted into a phase I call work-life integration. I loved my work so much that it just became part of my life. It wasn’t about separating work and life anymore—it was about integrating them.

Jeff Bezos talks about this. A lot of people talk about this. Just this morning, someone asked me in a meeting, How’s work?

I said, I don’t work.

They looked at me. What do you mean? Did you retire?

I said, No, I don’t work. I just live. My work is an expression of my life.

That’s what you’re doing, Ryan.

And here’s the crazy thing—people hear this and say, Yeah, I wish I had that.

First, they don’t believe it. That’s great that you found it, but I don’t think it’s real.

Then, they accept it but say, That’s great that you found it, but it’s not for me. I haven’t found it.

The truth is, we can help every person in our companies find meaning in their work. And it’s not just our obligation—it’s our responsibility. If someone works for us, we should help them find meaning in what they do every day.

It’s good business. But more importantly, it changes their experience of life and their growth. That’s why one of my favorite thinkers, Clay Christensen, called business and management the most noble profession.

It can be the noblest profession—if we help people grow, give them meaningful experiences, and let them leave work energized and proud of what they’ve achieved. Otherwise, they just leave exhausted, with nothing to say.

Ryan Heckman: And if we bring it full circle to private equity—it has a well-earned reputation for being difficult.

It’s no surprise that companies owned by private equity firms often lack well-being. If the CEO feels like they’re under fire every day, they’re going to treat their executive team a certain way. Then, the middle managers get treated a certain way. It’s a cliché, but it really does start at the top.

Rallyday isn’t going to change the entire private equity industry. But we hope that by producing exceptional returns, more firms will adopt these principles. We want to create a ripple effect. That’s why we make all of these innovations open source.

We spend a lot of time sharing our content and tools with competitors. We want them to use them. It’s our way of elevating the industry. And I hope that even through this podcast, maybe one private equity person listens and thinks, I’d like to do things a little differently. So, thank you for giving me the opportunity to share this. It’s been really fun.

Ashish Kothari: Ryan, thank you. I’m excited about what we’re doing together and how we’ll continue to partner.

Actions speak louder than words. You’re leading in a way that will bring results—not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because it works.

Like you, I came to this from a place of spirit. But then my mind kicked in, and I looked for evidence. The reality is, we can’t convince everyone just by shouting about it. We have to meet them where they are.

That’s why I found the language and the science to back this up. And the science is clear—when you invest in your people, help them flourish, and create environments where they thrive, you outperform.

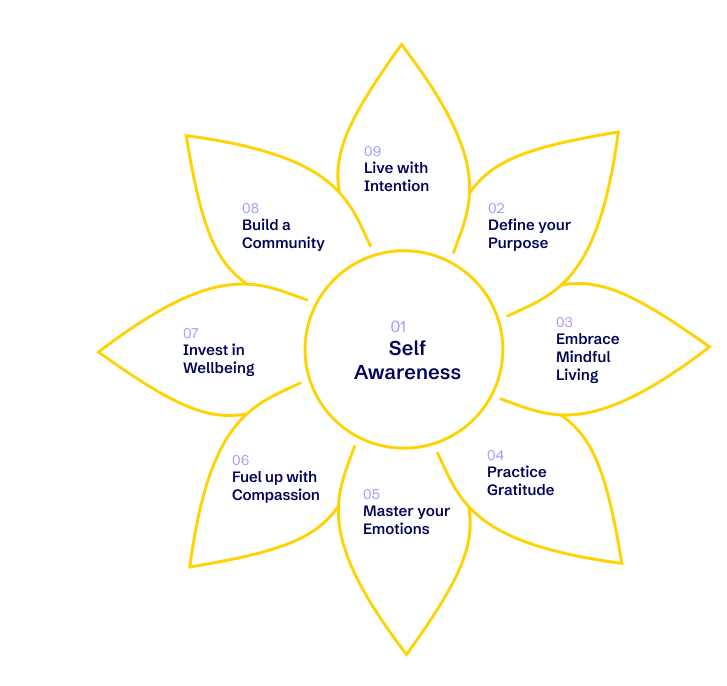

That’s why we say we’re all about:

1️⃣ Democratizing flourishing—helping everyone, from the frontline to senior leadership, integrate this work so they can flourish.

2️⃣ Making flourishing your competitive edge—because most companies are only tapping into 20–30% of their people’s potential.

If you can tap into that untapped human magic, over 6, 10, 15 years, I am convinced your returns won’t just be slightly better. They’ll be positively deviant—way beyond normal private equity returns.

Ryan Heckman: I can’t wait to use that in a fundraising conversation. I have so much conviction in this approach. And honestly—I’d rather lose doing it this way than win any other way. That’s how strongly I feel about it.

Our whole team at Rallyday feels the same way. Not every day is a happy day. But every day can be a joyful day—because we’re contributing to people’s lives. I can’t wait to do this again in five years and share how our positive deviance has played out.

Ashish Kothari: And thank you for teaching us, Ryan.

I feel like we’re just beginning this journey together.

I can’t wait to grow, learn, and build something meaningful with you.

Ryan Heckman: You’re only 45 minutes away—I look forward to seeing you again soon, Ashish.

Ashish Kothari: Absolutely. Cheers, my friend.

Ryan Heckman: Take care.